The Mathematics of Dobble

John Longley, School of Informatics,

University of Edinburgh

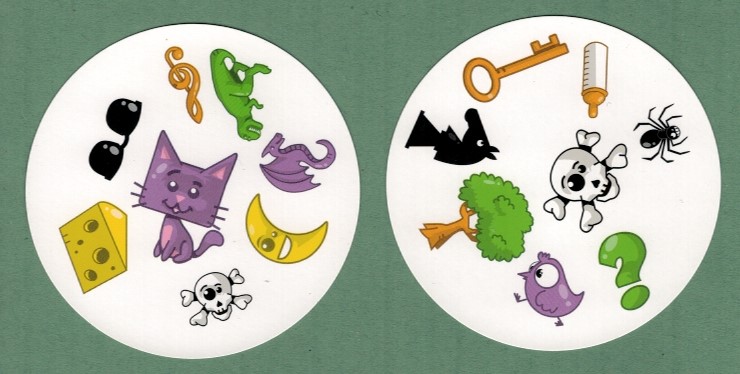

Dobble® is a fantastic card game developed by Zygomatic Games and published by Asmodee Group. It is widely available via Amazon and many other outlets. Besides being great fun to play, Dobble exhibits some remarkable and intriguing mathematical structure.

This educational and interactive website offers a gentle introduction to the maths behind Dobble, including its beautiful connection with projective geometry and its relevance to error-correcting codes. It also describes a variety of card tricks and demonstrations that illustrate this structure.

The main pages of this site (Parts I-V) are intended to be readable by anyone with basic school-level maths, but there are also links to pages offering further information for more mathematically advanced readers. In any case, do feel free to skip over anything that seems hard to follow – it may become clearer in the light of later sections.

To take advantage of the interactive features, you’ll need to be using a browser with Javascript enabled. For good results, Google Chrome is recommended.

The key property we’ve just described is actually pretty remarkable. Think for a moment about how you might set about constructing a Dobble pack for yourself – say, if you were on a desert island, with plenty of card, coloured pens, etc. How would you decide which symbols to put on which cards, so as to ensure that the fundamental rule is satisfied: any two cards share exactly one symbol?

The answer to this question is probably not obvious. So let’s begin by thinking about an easier version of the question. Let’s consider a tiny ‘baby’ version of Dobble, where each card carries just 2 symbols. I’ll refer to this as Level 2 Dobble – in contrast to the standard version which I’ll call Level 8 Dobble, because it has 8 symbols per card. (There are also versions of Level 6 Dobble commercially marketed as Dobble Junior, Dobble 1-2-3 and Dobble Kids.)

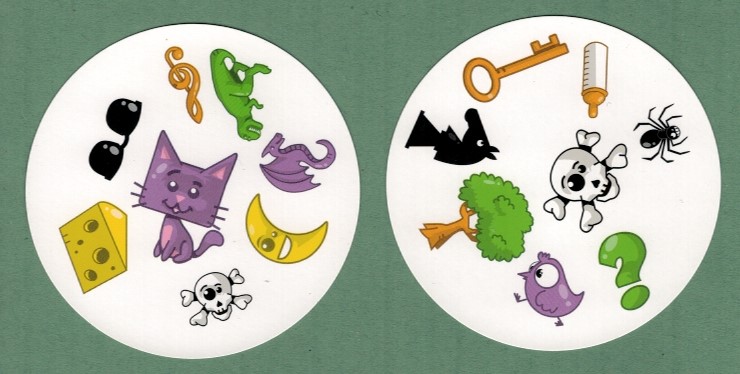

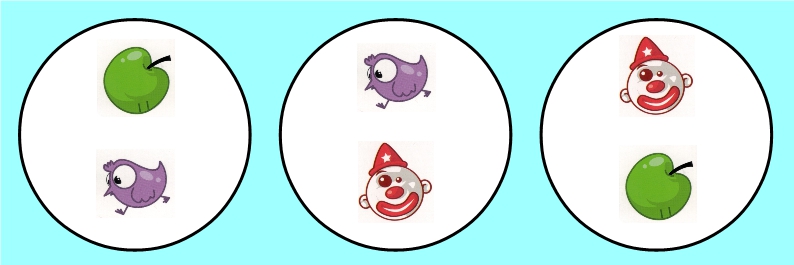

In Level 2 Dobble, we will have just 3 cards, and 3 distinct symbols: let’s take them to be the APPLE, the BIRD and the CLOWN. The question, then, is how we’d place these symbols on our cards (with 2 symbols per card) so that any two cards share exactly one symbol.

This is not hard at all. A moment’s thought shows that we can do it like this:

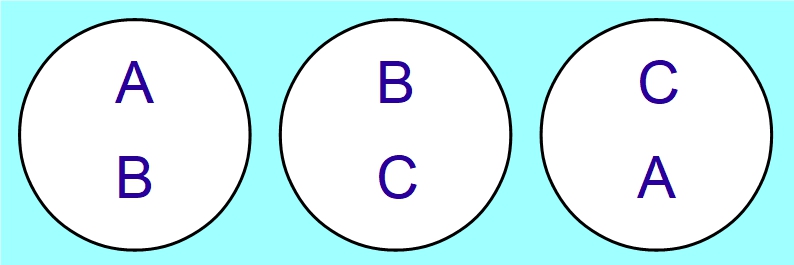

Replacing the 3 pictures by the letters A,B,C, our solution looks like this:

Now let’s take a step up, and see if we can design a Level 3 Dobble system: one with 3 symbols on each card. I’ll tell you for free here that this set should have 7 cards, with a pool of 7 distinct symbols, which we’ll take to be the letters A,B,C,D,E,F,G. (We shall see later where the number 7 comes from.) The challenge, then, is to fill 7 cards with 3 of these letters each, in such a way that any two cards share exactly one letter.

This makes for quite a good puzzle. See if you can do it for yourself, perhaps by trial and error (I've filled in the first circle to get you started). To add a symbol to any card (or replace an existing symbol), use the buttons A-G to select the symbol you want, then click on the appropriate position within the card (as illustrated by card 1). Once you’ve finished, click ‘Check answer’ to see if your solution is correct.

It's very possible that you come up with a solution that looks different from mine. However, there is also a sense in which all possible solutions to this puzzle are ‘essentially the same ’, and only differ in relatively superficial ways. In mathematical jargon, we say that all solutions are isomorphic. Click the link for more on this question of when are two Dobble systems ‘the same’.

Even more strikingly: we’ve already stated the fundamental rule that any two cards share exactly one symbol – but we can now also see that any two symbols share exactly one card. For example, suppose we pick the two symbols B and E. You will see that there’s one, and only one, card on which both these symbols appear. (In my solution, this is card 5.) The same is true whichever two symbols we pick.

Let’s organize what we’ve observed so far into two lists:

You’ll see that these two lists are in a sense ‘mirror images’ of each other: we can get one list from the other simply by swapping the roles of cards and symbols. In other words, there is apparently some kind of symmetry – or duality as mathematicians would call it – between cards and symbols. This idea of card-symbol duality will play quite a major role later on.

One consequence of this duality is that if we start with a Dobble system possessing these six properties, we can obtain another such system by swapping the roles of cards and symbols. To illustrate this, let’s take my solution to the puzzle above (spoiler alert!), with the cards numbered 1 to 7:

So it may seem that any solution to our Level 3 Dobble puzzle will lead by duality to a further solution. Actually, in this particular case, the situation is a little disappointing: comparing our original and dual solutions, it’s not hard to see that they are ‘the same’, in that we can obtain one from the other just by rewriting A,B,C,D,E,F,G to 1,2,3,4,5,6,7 respectively, and vice versa. So we may say that this particular Dobble system is actually self-dual. However, this doesn‘t always happen: we’ll see later that there are Dobble systems of Level 10, for instance, such that taking their dual leads to a genuinely different system.

Not every Dobble system is complete. For instance, suppose we took my Level 3 system and threw away Card 7: the one containing C,E,F. Then the remaining 6 cards would still form a Level 3 Dobble system according to our definition, but not a complete one, because there would now be no card containing both C and E. So a complete system is one with a card for any pair of (distinct) symbols.

Puzzle: Suppose we have a complete Level N Dobble system, where N ≥ 2. Staying with the same pool of symbols, would it be possible to add a further card and still have a Level N Dobble system? Explain your answer.

We’ll see later that complete Level N Dobble systems are actually very tightly constrained: there’s remarkably little freedom in how they are constructed. For instance, we’ll see that any Level N Dobble system must necessarily have the following properties:

The upshot of all this is that any complete Dobble system (of any level) will satisfy a list of six properties like those we listed for Level 3.

It seems clear that for a problem of this complexity, simple trial-and-error will no longer suffice: we will need some more systematic method. We will be describing one such method on the next page – though as we shall see, this will still leave a lot of questions unanswered. For example, it doesn‘t tell us whether a complete Level 13 Dobble system would be possible – and in fact the answer to this is currently unknown.

Before we come to all this, you might like to see whether you can construct a complete Level 4 system – or even harder, a complete Level 5 one! – just by trial-and-error reasoning. (These puzzles are more time-consuming than the Level 3 one, so you might prefer to skip them.)

For Level 4, the formula above tells us that the number of cards/symbols will have to be 42 − 4 + 1 = 13. So let’s use the letters A to M as our symbols.

For Level 5, the number of cards/symbols will have to be 52 − 5 + 1 = 21, so we’ll use the letters A to U. Warning: this puzzle is both time-consuming and difficult, unless you know the secret. If you succeed in doing it without any help… congratulations!

That completes our introduction to Dobble systems and the problem of constructing them. On the next page, we’ll describe a systematic method for building such systems, based on a deep and fascinating connection between Dobble and geometry. For more about this, proceed to Part II.